没有几种经济要素比大宗商品价格更重要。当大宗商品价格上涨时,它会将财富和实力从消费者转移到生产者;当价格下跌时,对于消费者而言,这几乎像是经济学里的免费午餐。大宗商品价格关系重大,其转折点对于全球经济很重要。眼前似乎就将迎来这样一个时刻。

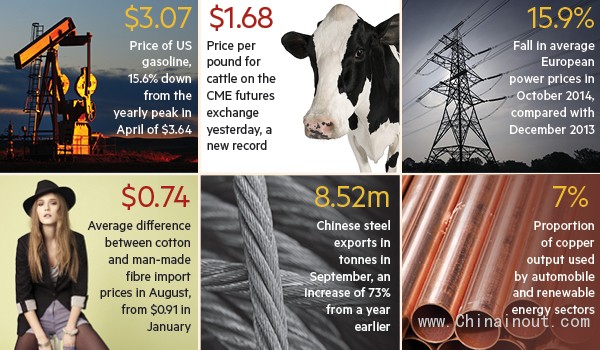

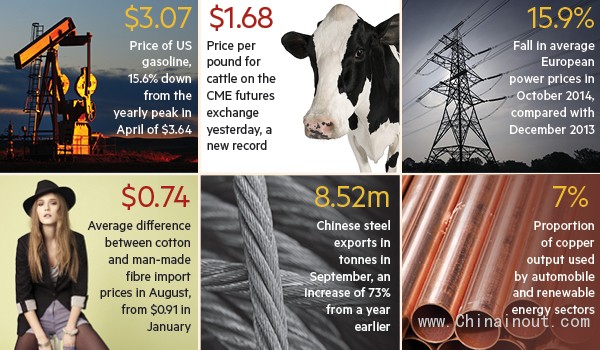

多种大宗商品价格都在下跌,有时是快速下跌。彭博(Bloomberg)大宗商品指数(大宗商品投资的一个基准)近期降至5年最低水平。多数大宗商品供应不断增加以及全球经济(包括中国经济)日益放缓正推低大宗商品价格。中国是很多大宗商品的最大消费国。不管是石油、玉米、铁矿石、煤炭、棉花还是铜,价格都在快速下跌。

国际货币基金组织(IMF)估计,全球大宗商品价格较今年年初下滑8.3%。在最近公布的《世界经济展望》(World Economic Outlook)报告中,IMF称,石油价格每桶下跌20美元将增加消费者的实际收入、提振消费国的国内需求和经济增速,同时冲击产油国的出口和需求。IMF估计,其净效应将是令全球GDP扩大0.5%,如果经济信心因此改善,这一数字可能会升至1.2%左右。Fulcrum资产管理公司董事长加文•戴维斯(Gavyn Davies)表示,这些估计数字是合理的,而且以任何标准衡量都”很大“。

根据凯投宏观(Capital Economics)经济学家安德鲁•肯宁厄姆(Andrew Kenningham)的计算,同样的变动将把6400亿美元财富(占全球GDP的近1%)从产油国转移到消费国。他表示:“我们的经验是,消费者一般会将意外收获的一半用于支出。那就是3200亿美元,约占全球GDP的0.5%。”

由于其他大宗商品价格会随着油价一起下跌,预计这种效应将放大,令全球增长受益,但在创造赢家的同时也会产生输家。增长预期所受的影响最为明显。2011年,当时市场预计大宗商品价格将长期处于高位,IMF预测,2014年巴西经济将增长逾4%,并且中期内将能够保持这一增速。如今,IMF预测,今年巴西经济将接近滞涨,中期增速将缓慢升至3%的水平。俄罗斯也是同样的命运,况且该国还要应对西方制裁的冲击。

然而,一些影响可能是复杂的。除了在不同国家之间出现资金再分配之外,同一国家中也会有赢家和输家。对于美国的驾车者而言,油价不断下跌的影响就像是减税,但这会冲击该国的页岩油行业。2011年,食品价格飙升对巴西农业是一种利好,但对于该国城市穷人而言却是一项沉重的负担。

汇率变动可能会令情况复杂化,因为多数大宗商品都是以美元计价。亚洲一些地区的货币兑美元汇率正在下跌。因此,高盛(Goldman Sachs)大宗商品研究主管杰夫•居里(Jeff Currie)表示,印度消费者没有看到巨大的好处,因为以印度卢比计算油价没有快速下跌,而在印尼等国,因应燃料价格下跌,政府也削减了燃料补贴,因此,消费者也没有看到完全的好处。在计入汇率和税收变动后,居里表示,美国是唯一一个消费者可能会看到巨大好处的国家。

作为一个消费和进口大户,欧元区将受益于大宗商品价格下跌,但经济学家警告称,欧洲不能高兴过了头。大宗商品价格持续下跌可能会令欧元区陷入彻底的通缩,这可能会促使消费者推迟购买行为,因为人们预测未来价格会继续下跌。

这都是理论,但可能会破坏欧洲央行(ECB)将中期通胀预期稳定在每年约2%的努力。巴克莱(Barclays)的托马斯•哈吉斯(Thomas Harjes)表示:“基于市场的通胀预期指标越来越显示,欧洲央行有丧失公信力的风险,市场可能认为其无法将通胀恢复到接近2%的目标水平,即便是在中期内。” (

中国进出口网)

Few economic forces are more important than commodity prices. When they rise they transfer riches and power from consumers to producers; when they fall, it is as near as anything in economics to a free lunch for consumers. With so much at stake, turning points are important for the global economy. Such a moment appears to be at hand.

Across a wide range of commodities, prices are falling and sometimes falling fast. The Bloomberg commodity index – which acts as a benchmark for commodity investments – fell to its lowest level in five years this week. Prices are being pushed down by the increasing supply of most commodities and a weakening global economy, including a slowing China, the world’s largest consumer for many of these raw materials. Whether it is oil, corn, iron ore, coal, cotton or copper, prices are falling quickly.

The International Monetary Fund estimates that global commodity prices are 8.3 per cent lower than at the start of the year. In its recent World Economic Outlook report, the IMF demonstrated how a $20-a-barrel oil price decline would increase the real income of consumers, boosting domestic demand and growth in consuming countries and hitting exports and demand in producer nations. The fund estimated the net effect would increase world gross domestic product 0.5 per cent alone, and if economic confidence were improved as a result, that figure could rise to about 1.2 per cent. Gavyn Davies, chairman of Fulcrum Asset Management, says the figures were plausible and by any measure “quite big”.

Andrew Kenningham, economist at Capital Economics, has calculated that an equivalent change would transfer $640bn – or nearly 1 per cent of world GDP – from oil producers to consumers. “Our rule of thumb is that consumers typically spend half of their windfall. This is $320bn or around 0.5 per cent of world GDP, ” he says.

With other commodity prices falling alongside oil, the effects can be expected to amplify, benefiting global growth but also creating losers as well as winners. The effects are most obvious in growth forecasts. In 2011, when commodity prices were expected to remain persistently high, the IMF forecast Brazil’s economy would expand more than 4 per cent in 2014, a rate it would be able to sustain into the medium term. Now it is expecting near stagnation this year with a slow climb towards a 3 per cent medium-term rate. Russia, which also has to deal with the added impact of western sanctions, shares the same fate.

Some effects can be complicated, however. As well as redistributing money between countries, there are also winners and losers within the same nation. While falling oil prices act as a tax cut for US motorists, it hits the country’s shale oil industry. In 2011, the surge in food prices was a boon to Brazilian agriculture but a huge burden on its urban poor.

Exchange rate movements can complicate the picture, since most commodities are priced in dollars. In parts of Asia currencies are falling relative to the dollar. As a result says Jeff Currie, head of commodities research at Goldman Sachs, consumers in India are not seeing big gains because oil prices in rupees are not falling fast, and in countries such as Indonesia, the government is offsetting lower fuel prices with cuts in fuel subsidies so, again, consumers have not seen the full benefit. After taking account of currency and tax changes, Mr Currie says the US is the only country in which consumers are likely to see a big benefit.

As a big consumer and importer, the eurozone will benefit from the turndown in commodity prices, but economists warn Europe must avoid getting too much of this good thing. Falling commodity prices could tip the eurozone into outright deflation, potentially delaying consumer purchases on the expectation of even lower future prices.

This is all theoretical, but could undermine efforts by the European Central Bank to stabilise medium-term expectation of inflation to about 2 per cent a year. Thomas Harjes of Barclays says: “Market-based measures of inflation expectations are increasingly indicating that the ECB is at risk of losing its credibility to return inflation back to the close-to-2 per cent target, even over the medium term.”